Jurisdictional Risk Part 3 – A Look at Argentina

What is the first thing that pops into your mind when you think about Argentina?

For some, it’s Lionel Messi or football (soccer for those in North America).

For others, it’s beef; I’ve been told that Argentina’s steakhouses are among the best in the world.

For investors, it’s most likely a thought about risk.

So why do investors associate Argentina with risk?

Since the 1930s, there have been issues with Argentina’s economy.

It has been a constant struggle to manage its national debt, control inflation, and now, within the last 20 years, deal with the consequences of a default on the national debt in 2001.

Going back to the early 90s, Argentina dealt with their inflation issue by pegging the peso, at par, with the U.S. dollar.

Further, the government privatized numerous state-owned and operated businesses to stimulate the economy and, of course, provide a much needed boost to the government’s treasury.

In 1998, however, things began to unwind, as debt continued to grow and the boom created by the privatization of the state-owned companies diminished.

Over the next 3 years, things progressively got worse, and eventually, it led to Argentina’s now famous default on their national debt in 2001 – roughly US$93 billion.

The situation spiralled out of control.

The peso took a massive hit.

Bank deposits were frozen.

The unemployment rate rose to over 22% and social unrest followed.

From this point onward, the country has never really been able to “right the ship†as they say.

To be honest, it really doesn’t surprise me, either.

As debt levels begin to rise and reach or exceed that of GDP, historically speaking, there is no turning back.

Not only is rising debt an issue from an economic standpoint, but socially, easy money becomes a part of the culture – it’s hard to break.

Applying this to Argentina’s situation, I really see no discernible changes in the obviously flawed government policy that led to this mess.

You can’t fix a debt issue with the same policies that created the issue in the first place.

Like so many countries, these days, governments have let their debt load rise to a point where they can’t even service the interest (at reasonable rates) on the debt.

Rather than default, governments or central banks choose to lower interest rates and begin the process of spurring inflation.

Inflation, however, like most things in life, is a double-edged sword.

Yes, you are able to inflate away your debt by de-valuing your currency, but it comes at a high cost.

First, you can’t control it.

Inflation isn’t like a light, you can’t turn it on and off at will.

Second, inflating away debt destroys the middle class, the very people whom government’s say they are trying to help.

SIDE NOTE: It’s estimated that Argentina’s annual inflation is an astounding 40%. Remember, the U.S. Federal Reserve has openly stated on numerous occasions now that it wants to trigger inflation within the U.S. economy. Inflation will devalue the USD and, over time, allow payback and the servicing of the national debt. I understand the intrigue of the idea, but the fact is, it can’t be controlled and, unfortunately, comes at a huge cost. Readers take note of the situation in Argentina and the numerous other examples we have seen throughout history. None of the situations are exactly alike, some worse than others. Bottom line, it doesn’t ever end well for the average Joe.

It’s a crazy, never ending loop.

While Argentina is particularly bad at managing its debt, it isn’t alone.

Most of the world, especially due to the Covid-19 pandemic, has elevated their debt levels to realms that are impossible to service at healthy or normal interest rates.

We are truly living at an interesting juncture in human history.

So, with this in mind, as resource investors I think that there are 2 main questions that need to be asked.

The Current Situation

First, from an economic standpoint, what is the current situation in Argentina?

Argentina continues to struggle with its current financial situation.

They have defaulted on their debt for a ninth time since 2001 and have an economy which is estimated to contract by 12% in 2020.

The latest default is linked to a US$57B IMF bailout in 2018, which, at the time, was coined as a ‘standby financing’ which would allow the economy to recover and put Argentina in a position to begin paying off their debt.

The economic recovery didn’t happen and the Covid-19 pandemic certainly hasn’t helped, but is hardly the main reason for the failure.

It’s obvious that this is a continuous loop of defaults, inflation and bailouts.

SIDE NOTE: Argentina’s international credit rating with Standard & Poor, Fitch and Moody’s is ranked alongside countries like Ecuador, Venezuela, Lebanon, and Congo. These aren’t the countries you want to be associated with when it comes to economic prosperity.

In eerily similar fashion, today, Argentina is in the midst of negotiations with the IMF on restructuring their debt and delaying payback until 2024.

This is a key negotiation for both parties.

From the IMF’s view, they just want to get paid, and there’s nothing wrong with that.

My guess is that the IMF wants to find terms that don’t completely tie the Argentine government’s hands, but are stiff enough to prevent the chance of another default in the future.

As the Argentine government states, they don’t want to default on their debt and this is why they are looking for further wiggle room in the payback structure.

In my view, prevention of a future default on debt is inextricably linked to a cut in government spending – without a doubt.

With that said, given their past and the fact that there are midterm elections on the horizon, I find it highly unlikely that this will happen.

The government, however, has announced new stiffer capital controls, in addition to those adopted in 2019, which are aimed at stabilizing the country’s foreign currency reserves.

The foreign currency reserves, mainly their holdings of USD, are vitally important because their debt is denominated by USD.

Citizens are being dissuaded from purchasing USD and selling pesos, and at the moment, they can only acquire a maximum of US$200 per month.

Further, there’s a new 35% tax on USD denominated purchases, which is on top of the 30% solidarity tax that’s already in place.

Corporations, like Argentina’s citizens, are subject to similar controls that are aimed at diminishing the export of USD.

This mainly affects how companies distribute dividends, export goods and service their USD denominated debt, although new recent regulations were recently put in place to solve these issues, as mentioned below.

SIDE NOTE: The Peso is losing its value at such a high rate that nothing of significant value is priced in it – Real estate, vehicles or any other big ticket items are all priced in USD.

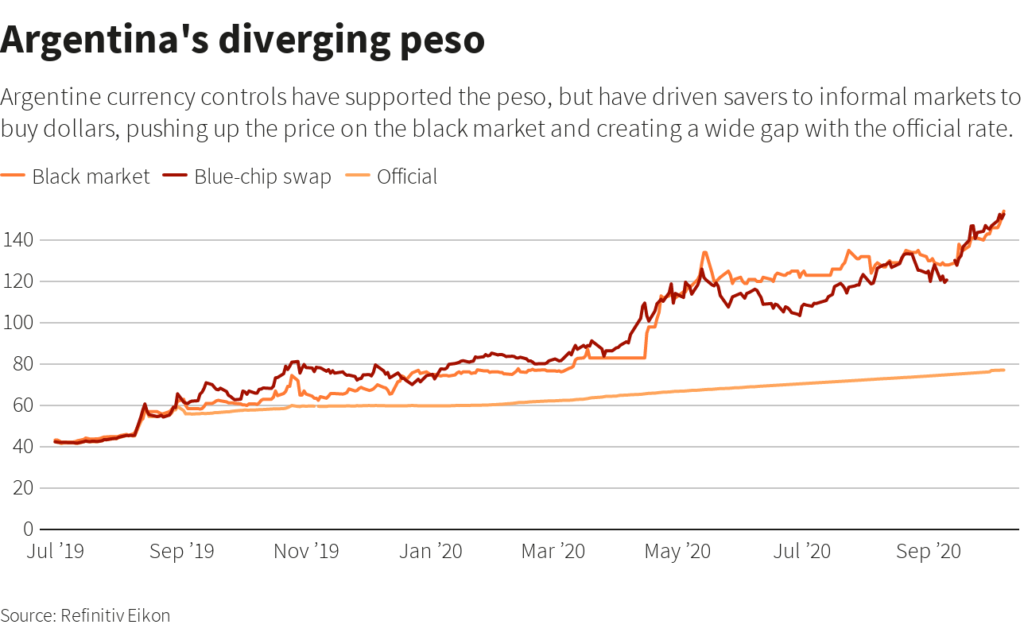

With rampant inflation and stringent capital controls, a black market for USD has sprung up.

The official exchange rate – 74ish Pesos to 1 USD.

The unofficial or black market rate – 150ish Pesos to 1 USD – and rising fast.

As you can see, for those looking to acquire more dollars or dollar denominated services/products, the cost is enormous.

Moreover, these restrictions, while bringing short-term stability to the foreign currency reserves, without a doubt, have cast further doubts about the investment attractiveness of Argentina.

Mining Investment Attractiveness of Argentina

So now, as resource sector investors, what’s the current mining investment attractiveness of Argentina?

This is a great question and the whole point of this article.

The fact is, if you just read the headlines surrounding the current risk in Argentina, you would be missing a big part of the equation.

As always, there’s never a ubiquitous answer to any question, it always depends.

In this case, it depends on:

- Type of Company – At the moment, junior mining companies that are exploring and/or developing projects are able to take advantage of the unofficial exchange rate between the Peso and U.S. dollar by completing what some of the companies call a “Blue Chip Swap (BCS)â€.

A BCS is when a company imports USD into the country and invests it into blue chip stocks on the Argentine exchange.

After holding it for a period of time, they then liquidate the position and are able to take the cash out and convert it at the unofficial exchange rate – completely legal.

To note, all the companies that I spoke with use the official rate to set budgets.

For companies that only burn cash, this is a major plus.

For producing companies, it’s a little different.

As I stated earlier, there are restrictions on USD out flows – dividends, profits and debt payments.

With that said, the government has relaxed some of the restrictions in light of the importance of mining.

- Reduce the export duty for mining exports from 12% on FOB value to 8%

- Include mining activity in the strategic plan for the reactivation of the Argentine Economy.

Further, the Central Bank Of Argentina (BCRA) stated the following in ‘Communicacion A 7123’:

- Foreign currency brought into Argentina and liquidated into pesos by export companies will enable those companies to: (i) pay off capital and interest of foreign loans (provided that repayment terms are greater than one year) and (ii) repatriate capital, which we understand includes dividends, from investment projects once they have started operations.

- All this is subject to certain conditions (that the mining industry meets) such as the following: 1. The exports refer to productive projects that generate export goods and / or that allow substituting the import of goods; 2. The foreign currency from exports is entered into the country as from October 2, 2020; 3. Those who opt for this regime designate a financial entity that will do the follow-up. For those who opt for this regime, the amounts of foreign currency that they will be able to acquire for imports are also increased (50% of what is exported).

- Location – As they say in real estate “location, location, location,†and the statement applies to the junior mining world.

As I mentioned in Part 1 of the series, it’s key to understand the risks at the national level and work your way progressively down to the state or province then to the region or county, and finally, at the local town or city level.

As you progress toward the exact location of a prospective company’s project, you will uncover any hidden risks at the upper levels.

In terms of Argentina, it’s all about which province the project is located.

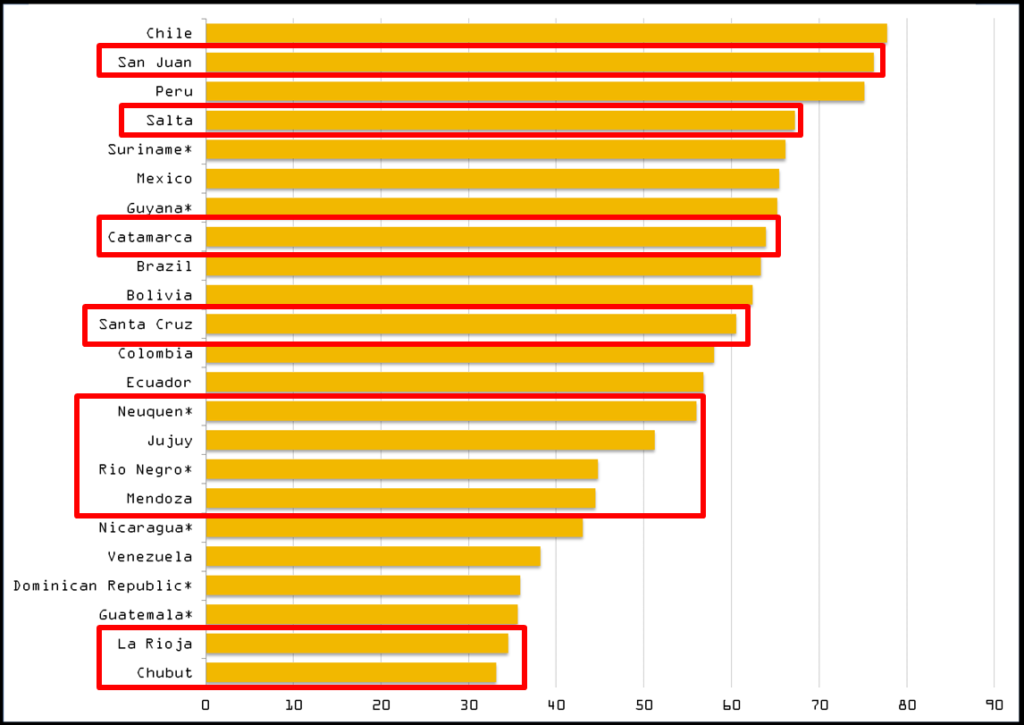

San Juan and Salta, in particular, are great provinces in which to be a mining company.

Both have the history, mining law and general positive attitude toward mining.

Here’s a look at how the Fraser Institute ranks mining investment attractiveness in Latin America.

Source: 2020 Fraser Institute Rankings

As you can see, San Juan and Salta are ranked #2 and #4 in Latin America and only trail Chile and Peru, which are widely considered some of the best places in the world for mining investment.

In Argentina, the provinces control the mining law and collection of taxes, which are capped at 3% of revenue.

Now that we have an idea of Argentina’s current situation and how it affects junior mining companies, it’s pertinent to explore risks that may occur in the future.

I think there are 3 main risk factors that we need to explore:

- Nationalization of Assets – The nationalization of assets is a very real risk.

Unfortunately for investors in the resource sector, it does happen and, more specifically with Argentina, it has happened once fairly recently.

In 2012, the Argentine government voted to re-nationalize the country’s largest oil company, YPF.

For context, YPF was once an entirely state-owned company until the spree of privatization in the 90s, which resulted in a large portion of the company being sold off to foreign interests.

The YPF privatization was highly criticized in Argentina since other countries in Latin America kept their state-owned oil & gas companies (Petrobras in Brazil, Pemex in México, etc.) in order to maintain sovereignty over these resources.

At the time, Christina Fernandez de Kirchner (now VP under Alberto Fernandez) was President and justified the re-nationalization on the grounds that the private company didn’t boost the oil and natural gas production needed to keep up with local demand.

This move has and will continue to haunt Argentina moving forward.

So, are junior mining companies at risk of having their projects or mines nationalized?

No one can say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ without a doubt.

What I will say is that at least a portion of the risk is dependent upon the type of company.

In my view, the companies that are exploring or developing a project(s) in Argentina are less likely to see their projects nationalized than a producing mine.

Junior mining companies require both cash to burn and a niche skill set to effectively explore and develop projects.

I highly doubt this is an appealing prospect to a government.

Second, while the risk is higher for producing hard rock miners, I still think that there are many barriers to making nationalization an appealing alternative for governments.

Why nationalize and have to operate a mine when you can just tax it?

Further, while YPF is a recent example of nationalization in Argentina, I wasn’t able to find an example of a fully private company that was nationalized by the government.

While I know the government is fully capable of stealing, I’m less inclined to believe that is the course of action they would prefer to take.

- New Tax Regime – It’s my contention that the greatest risk to mining companies within Argentina is the risk of increased taxes in the future.

A new tax regime could remove a good portion, if not all, of the profitability of a mine.

How likely is it to happen?

That’s a really hard question to answer.

There are a couple of scenarios that I think could make taking a larger chunk of the mining company profits tempting.

- A major spike in the metal prices – In my view, mining is one of the few sectors that I think will show major growth over the next few years. This growth will be driven by high metal prices.

- Brink of another default – As I mentioned, I don’t see any dramatic policy changes related to spending coming anytime soon. This is a problem moving forward as it appears that their current loop of borrow, inflate, and default will most likely continue into the future without a drastic change to how the country is run.

While the threat of higher taxes is a risk to mining companies in Argentina, it may only be a threat to future mines.

It should be noted that junior mining companies, by current law, lock in tax rates for 30 years of production once a Feasibility Study (FS) has been completed on their project.

Now, this doesn’t mean laws can’t be changed – they can be.

But I can’t help but think that the fallout of such measures would cause much more damage than any short-term gain.

Ecuador is a great example for Argentina.

Their institution of a windfall tax had devastating effects on the mining sector.

With a new government in place, the impact of the windfall tax was re-assessed and, with the help of Wood Mackenzie, Ecuador revamped their tax regime to better reflect best practices worldwide.

Low and behold, investment dollars from investors and major mining companies have begun to flow back into the country.

Ecuador is by no means a perfect jurisdiction for mining, but it’s getting better and has outstanding geological potential.

Mining is a huge part of Argentina’s economy, especially in provinces like San Juan and Salta where mining accounts for more than 80% of the province’s revenue.

They can hardly afford to lose it.

For perspective, for every US$1 that leaves the country because of mining, US$24 comes in.

Higher taxes on mining aren’t the answer to Argentina’s debt issues.

If anything, the government should make it a priority to enhance Argentina’s mining investment attractiveness, not further destroy it.

In the end, I think that the provinces that are pro-mining and have a history of upholding its mining law will remain that way.

With regards to the Federal government, it’s much harder to gauge.

Mining Companies in Argentina

Many of the biggest senior gold and silver miners have operations or are developing mines in Argentina.

Here’s a list of a few of them:

Pan American Silver (PAAS:TSX) – Operate their Manantial Espejo mine in Santa Cruz and owns the Navidad project in Chubut.

Fortuna Silver (FVI:TSX) – Recently spent US$300M in CAPEX to construct their Lindero Mine, which is located in Salta.

Barrick Gold (ABX:TSX) – Operate their Veladero mine and the Lama project and new exploration areas in San Juan. In 2020, Barrick also entered the Salta province by signing an earn-in agreement on the El Quevar silver project.

SSR Mining (SSR:TSX) – Operate Puna which is comprised of the Chinchillas mine and Pirquitas processing facility which is located in Jujuy.

Newmont (NGT:TSX) – Operates the Cerro Negro mine in Santa Cruz.

McEwen Mining (MUX:TSX) – Operate their San Jose silver-gold mine in Santa Cruz jointly with the Peruvian company Hochschild, and also owns the large-scale Los Azules copper project in San Juan.

Yamana (YRI:TSX) – Operate their Cerro Moro in Santa Cruz.

Austral Gold (AGD:ASX) – Operate their Casposo mine in San Juan.

First Quantum Mineral Ltd. (FM:TSX) – Advancing their Taca Taca project in Salta.

Glencore PLC (GLEN:LSE) – Operate Bajo de la Alumbrera project in Catamarca, jointly with Goldcorp and Yamana Gold, and also owns Pachon in San Juan.

A few junior mining companies that are exploring and developing projects in Argentina:

AbraPlata Resources (ABRA:TSXV) – PEA Level Project

JoseMaria Resources (JOSE:TSXV) – PFS Level Project

Filo Mining Corp. (FIL:TSXV) – PFS Level Project

Aldebaran Resources (ALDE:TSXV)

Golden Arrow Resources (GRG:TSXV)

Neo Lithium (NLC:TSXV)

Lithium Americas Corp. (LAC:TSE) – Under construction

Concluding Remarks

In my view, protecting your downside risk by investing in companies that are selling for less than their value is an essential part of making money consistently in the junior resource sector.

The higher the delta between price and value, the more downside protection you have.

I believe, therefore, that it allows for investment in opportunities in some of the riskiest jurisdictions on the planet.

Now, there’s a thin line here, you do have to understand what you are getting into and how the company you are investing in is going to navigate that risk and, ultimately, make you money.

There are going to be some situations that just aren’t worth the risk or the time commitment.

Personally, I think that I have a good understanding of the situation in Argentina.

There is risk.

With that said, I’m ready to make investments in junior mining companies operating there if they fit my framework for an investable company.

As always, the thesis starts with the people running the company.

Do they have the IQ, experience and backing to execute the action plan which they are pitching?

Second, if it’s the right people, is the company selling at a discount to its value?

The higher the discount to value, the more appealing the opportunity is.

Third, where is the project located?

Personally, I want to concentrate on San Juan and Salta.

I put my money where my mouth is and have put this framework to use.

Last year, I invested in AbraPlata Resources at $0.033/share.

It’s run by the right people.

At the time of investment, the company was selling for a steep discount to value.

Finally, their Diablillos project is located in Salta.

All the right ingredients needed to protect my downside risk, plus it had huge upside potential if the company executes on their plan.

Today, the share price is roughly $0.38, a more than 10 fold increase and, at the moment, a vindication of the original investment thesis.

Investing your money in countries like Argentina come with risk, but if you have done your homework and have applied a framework for decision making, it’s my contention that you have given yourself the best opportunity to be successful.

Finally, there’s nothing wrong with avoiding risky jurisdictions, just remember any country/government is capable of stealing your money.

Use the Coupon Code DILIGENT to get 25% off a subscription to and get my best investment ideas and commentary first.

Until next time,

Brian Leni P.Eng

Founder – Junior Stock Review Premium

Disclaimer: The following is not an investment recommendation, it is an investment idea. I am not a certified investment professional, nor do I know you and your individual investment needs. Please perform your own due diligence to decide whether this is a company and sector that is best suited for your personal investment criteria